Lab 05 Examples (Satisfiability)¶

Logical and Bitwise Operators, Truth Tables, and Satisfiability

Click <shift> <enter> in each code cell to run the code. Be sure to start with the #include directives to load the required libraries.

// For Lab 05, we are limited to these includes.

// Other libraries that can do the set or binary operations for us are not allowed.

// For example, DO NOT include <bitset> or <set>.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <cmath>

Logical Operators and Bitwise Operators¶

We've previously looked at the logical operators && (AND), || (OR), and ! (NOT), and the bitwise operators & (AND), | (OR), and ^ (XOR).

We've also looked at the bitshift operators << (left shift) and >> (right shift).

We have not yet mentioned the bitwise NOT operator ~ (tilde).

The logical NOT operator ! negates a boolean expression and will always evaluate to either true or false, while the bitwise NOT operator ~ inverts all bits of its operand.

| Decimal | Binary | Bitwise NOT ~ |

Logical NOT ! |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 1111 | 0001 (true) |

| 1 | 0001 | 1110 | 0000 (false) |

| 2 | 0010 | 1101 | 0000 (false) |

| 3 | 0011 | 1100 | 0000 (false) |

| 4 | 0100 | 1011 | 0000 (false) |

| 5 | 0101 | 1010 | 0000 (false) |

| 6 | 0110 | 1001 | 0000 (false) |

| 7 | 0111 | 1000 | 0000 (false) |

auto int2bitstring = [](unsigned int n, int bits = 32) {

std::string result;

for (int i = bits - 1; i >= 0; --i) {

result += (n & (1 << i)) ? '1' : '0';

}

return result;

};

int a = 0;

int b = 1;

int c = 2; // Binary: 010

// Logical NOT operator

std::cout << "int a = " << a << ", !a = " << !a << ", !a = " << int2bitstring(!a) << std::endl;

std::cout << "int b = " << b << ", !b = " << !b << ", !b = " << int2bitstring(!b) << std::endl;

std::cout << "int c = " << c << ", !c = " << !c << ", !c = " << int2bitstring(!c) << std::endl << std::endl;

// Bitwise NOT operator

std::cout << "int a = " << a << ", ~a = " << ~a << ", ~a = " << int2bitstring(~a) << std::endl;

std::cout << "int b = " << b << ", ~b = " << ~b << ", ~b = " << int2bitstring(~b) << std::endl;

std::cout << "int c = " << c << ", ~c = " << ~c << ", ~c = " << int2bitstring(~c) << std::endl;

int a = 0, !a = 1, !a = 00000000000000000000000000000001 int b = 1, !b = 0, !b = 00000000000000000000000000000000 int c = 2, !c = 0, !c = 00000000000000000000000000000000 int a = 0, ~a = -1, ~a = 11111111111111111111111111111111 int b = 1, ~b = -2, ~b = 11111111111111111111111111111110 int c = 2, ~c = -3, ~c = 11111111111111111111111111111101

unsigned int a = 0;

unsigned int b = 1;

unsigned int c = 2; // Binary: 010

// Logical NOT operator

std::cout << "unsigned int a = " << a << ", !a = " << !a << ", !a = " << int2bitstring(!a) << std::endl;

std::cout << "unsigned int b = " << b << ", !b = " << !b << ", !b = " << int2bitstring(!b) << std::endl;

std::cout << "unsigned int c = " << c << ", !c = " << !c << ", !c = " << int2bitstring(!c) << std::endl << std::endl;

// Bitwise NOT operator

std::cout << "unsigned int a = " << a << ", ~a = " << ~a << ", ~a = " << int2bitstring(~a) << std::endl;

std::cout << "unsigned int b = " << b << ", ~b = " << ~b << ", ~b = " << int2bitstring(~b) << std::endl;

std::cout << "unsigned int c = " << c << ", ~c = " << ~c << ", ~c = " << int2bitstring(~c) << std::endl << std::endl;

unsigned int a = 0, !a = 1, !a = 00000000000000000000000000000001 unsigned int b = 1, !b = 0, !b = 00000000000000000000000000000000 unsigned int c = 2, !c = 0, !c = 00000000000000000000000000000000 unsigned int a = 0, ~a = 4294967295, ~a = 11111111111111111111111111111111 unsigned int b = 1, ~b = 4294967294, ~b = 11111111111111111111111111111110 unsigned int c = 2, ~c = 4294967293, ~c = 11111111111111111111111111111101

The binary output for the bitwise negation is exactly what one would expect, but the decimal representation might be surprising.

This is because we're seeing the two's complement representation of the negative integers. There's more we could say about what this is, but it isn't directly related to satisfiability, so for now, we'll just note that negative numbers are stored in the upper half of the range of values for a given integer type. That's why we see those large decimal values for the unsigned integers and negative decimal values for the signed integers.

Since the bit strings for the bitwise negations are exactly what we'd expect, we can trust that any bitwise NOT ~ used to investigate satisfiability will work as expected.

Truth Tables and Satisfiability¶

A boolean expression is satisfiable if there exists at least one assignment of truth values to its variables that makes the expression evaluate to true.

A satisfiability expression with two variables has $2^2 = 4$ possible arrangements of truth values:

| A | B | NOT B | (A OR (NOT B)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | true | true |

| false | true | false | false |

| true | false | true | true |

| true | true | false | true |

A satisfiability expression with three variables has $2^3 = 8$ possible arrangements of truth values. Below is an example where only one permutation is satisfiable. (A AND B AND (NOT C)):

| A | B | C | NOT C | (A AND B AND (NOT C)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | false | true | false |

| false | false | true | false | false |

| false | true | false | true | false |

| false | true | true | false | false |

| true | false | false | true | false |

| true | false | true | false | false |

| true | true | false | true | true |

| true | true | true | false | false |

A boolean expression is unsatisfiable if there is no assignment of truth values to its variables that makes the expression evaluate to true.

// Satisfiability calculations using variables A, B and C

int A = 1; // true

int B = 1; // false

int C = 0; // false

std::cout << "A && B = " << (A && B) << std::endl; // AND

std::cout << "A || B = " << (A || B) << std::endl; // OR

std::cout << "!A = " << (!A) << std::endl; // NOT (logical)

// Example: (A || !B)

std::cout << "A || !B = " << (A || !B) << std::endl;

// Example: (A && B && !C)

std::cout << "A && B && !C = " << (A && B && !C) << std::endl;

// Example: (((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C))

std::cout << "((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C) = " << (((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C)) << std::endl;

A && B = 1 A || B = 1 !A = 0 A || !B = 1 A && B && !C = 1 ((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C) = 1

Truth Table for (((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C))

| A | B | C | (A && B) | (B || C) | (A && B) && (B || C) | (B && C) | !(B && C) | ((A && B) && (B || C)) && !(B && C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | false | false | false | false | false | true | false |

| false | false | true | false | true | false | false | true | false |

| false | true | false | false | true | false | false | true | false |

| false | true | true | false | true | false | true | false | false |

| true | false | false | false | false | false | false | true | false |

| true | false | true | false | true | false | false | true | false |

| true | true | false | true | true | true | false | true | true |

| true | true | true | true | true | true | true | false | false |

Relating Satisfiability to Logic Circuits¶

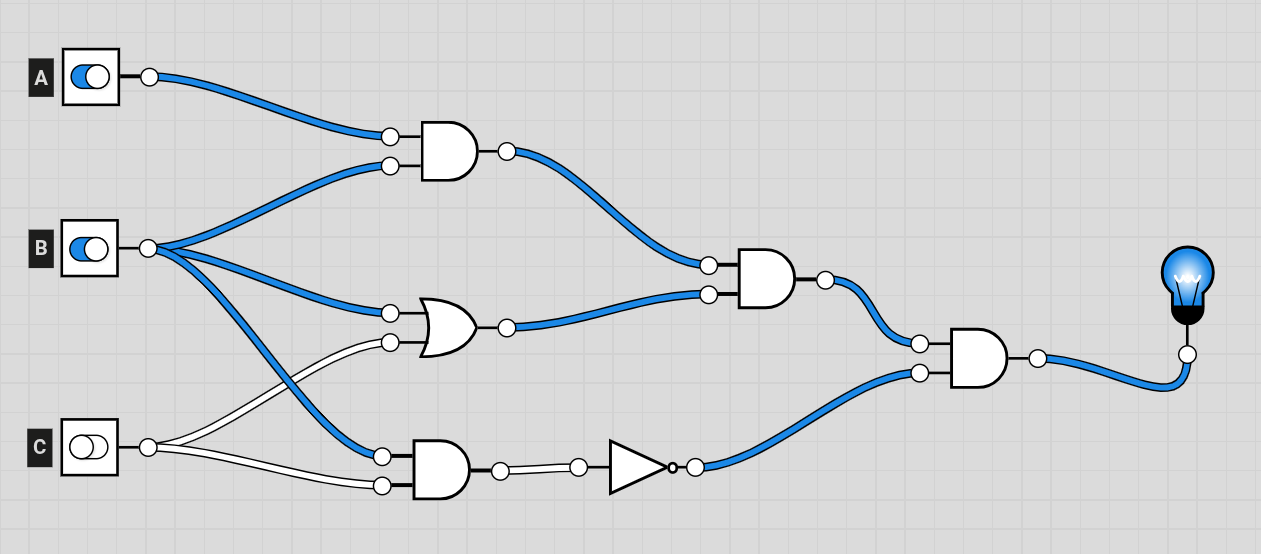

Here is an example of a logic circuit created in Logic.ly to visualize satisfiability for the expression from above.

((A AND B) AND (B OR C)) AND NOT(B AND C).

Experiment with your own designs on the Logic.ly demo site.

The demo site will not let you save or export your designs, but the full version of Logic.ly is available on the Engineering vLAB.

Implementing Satisfiability in C++¶

The code above showed satisfiability for one arrangement of variables A=true, B=true, C=false. The program we write should show the result of not just one arrangement of variables for a given expression, but all permutations and indicating which are satisfiable.

In order for our program to determine satisfiability, we should consider how to represent the truth table values in a data structure.

- One option is to use arrays or vectors of booleans to represent the truth table columns. Then compare the values at each index to determine the result of the expression.

std::vector<bool> A = {false, false, true, true};

std::vector<bool> B = {false, true, false, true};

for each row of the truth table

this_row_truth_value[i] = (A[i] || !B[i]);

- With the above approach, we used

logicaloperators to compare each row of the truth table one at a time. Could we instead compare all rows at once usingbitwiseoperators instead? Bitwise operators act on all bits of a number at once.

| A = 0011 | false, false, true, true |

| B = 0101 | false, true, false, true |

- Recognize that

0011(the truth table values for column A) is just a number. In this case for a 2-variable truth table, it is the integer3. Similarly,0101(the truth table values for column B) is just the integer5. - In the lab assignment, we are working with a 3-variable truth table, so the numbers representing the truth table columns will not be the same as for a 2-variable truth table.